You are here

An Employability Roadmap for Placements

Dr Lisa Taylor Associate Dean for Employability, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of East Anglia

Email: Lisa.Taylor@uea.ac.uk

Twitter: @drlisataylor

What is employability?

What is employability? is the $64,000 question that is often asked. Employability is very difficult to define, and cannot be compartmentalised to a point in time, or as a single concept. The definition of employability is a fluid concept, depending on your perspective. However, what is agreed is that it is a very personal concept, unique to each individual (Crisp et al, 2019), and needs to be embedded in every aspect of the student journey (Tibby and Norton, 2020). Agency and engagement at an individual level is required with a person centred approach (Cole and Tibby, 2013) and is everybody’s business to make it a genuine nature and nurture approach (Taylor, 2020a). Personal and professional identity formation underpins a student’s ability to successfully plan and develop their future work and career (Bennett, 2018; Alt, 2015) and their individual contribution to the wider workplace and society.

Students need to be prepared for lifelong and lifewide learning and career development (Clouston et al, 2018; Failey-Murdoch and Ingram, 2017; Saviskas, 1997; Saviskas and Porfeli, 2012; Super, 1980; Taylor, 2020a). Employability and continuing professional development are key components of a health profession student and subsequent professional journey (Taylor, 2016). This journey involves the development of transferable employability resources such as skills, abilities, attitudes and behaviours, that individuals can use throughout their careers (Inkson et al, 2015), and that placements offer students a wealth of opportunity to develop. However, these employability opportunities need to be made explicit to students.

There may be a belief that placements are about developing professional clinical skills ready for employment as a health professional. However, a health professional’s career will have multiple employment destinations with multiple individual employability journeys in between (Taylor, 2016), and students need to be prepared and able to take ownership of that employability journey. Therefore, placements are more than just about clinical skills or getting a job at the host site, they are about quality personalised learning experiences, equipping individuals for lifelong employability learning (Taylor, 2020, Taylor, 2020b). Some of the top employability attributes that employers are looking for in graduates are teamwork, interpersonal skills, listening, problem solving and taking responsibility (Hooley, 2020), key attributes that can be developed through any model of placement provision. Placements also help students to transition into the workplace (Tomlinson, 2012), developing confidence and competence in a long list of requirements for health professionals, in addition to clinical skills (Whitehead and Brown, 2017).

Clinical skills are obviously crucial for health professionals – but we need to prepare our students for fulfilling careers – which involves them being aware of who they are, what they have to offer and what they want relating to their employability and career development. Placements are a perfect conduit to facilitate that development, but is the employability potential for placements really fulfilled for students when on placements? Employers are looking for more than just skill development – behaviours, qualities, attitudes are as important to enable individuals to maximise their potential (Kay, 2013, Taylor, 2016). An employability profile for health students suggests that cognitive skills, generic competencies, personal capabilities, technical ability, business and organizational awareness, and practical and professional elements are the main elements of employability (Kubler and Forbes, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c), which are offered in abundance during placements. However, these employability elements need to be made explicit to students, for them to maximize the potential of their placement experience from an employability point of view.

Models of employability and placements

Employability is multifaceted and complex and engagement between students, education and employers is essential to determine the priority facets of employability from all perspectives. A number of employability models within the literature capture the multifaceted nature of employability.

Bennett’s (2017) literacies for life model of employability

This focuses on the metacognitive approach to employability. Students need to understand their thinking and learning processes, with higher education playing an important role in the early stages of this lifelong process of employability and career development. Reflection aids individuals to gain a self identity, agency and ownership of their employability, and is key for integrating work with everything else that is in an individual’s life (Harrington and Hall, 2007). The reflective element of placements and portfolio building, facilitates this crucial metacognition process within employability.

Bridgstock presents graduate employability 2.0 (http://www.graduateemployability2-0.com/)

A model of employability which focusses on social connectedness and relationships and employability. Placements provide the opportunity for students to build connections and relationships that will impact on their future employability and career development.

Tomlinson (2017) presents a graduate capital model of employability

Outlining 5 areas of capital impacting on employability. This model helps to address the challenges of transitions into employment and early career management. Health professions graduates can face challenges in the transition into the workplace and preparation and support for this transition is essential. Placements offers an insight for students as to what the world of work is like, and the process of transition into an autonomous practitioner.

The three models of employability below reinforce the breadth of employability, in addition to the knowledge and skill development of individual professional subjects. These models demonstrate the multiple facets of employability, reinforcing that placements cannot just focus on professional knowledge and skill development, and additional employability learning needs to be facilitated, to maximise the potential of employability related placement learning for students.

Career EDGE, Dacre-Pool and Sewell*

|

Career Development Learning |

|

|

E |

Experience (work and life) |

|

D |

Degree subject knowledge skills and understanding |

|

G |

Generic skills |

|

E |

Emotional intelligence |

|

Employability needs self efficacy, self esteem and self confidence, with reflection and evaluation |

|

*original model 2007 but updated in 2020

4 Components of employability, Hillage and Pollard (1998)

|

Assets |

Knowledge, skills, attitudes |

|

Deployment |

Career management, job searching and strategic approach |

|

Presentation |

Curriculum vitae, references, interview technique, work experience |

|

Context of personal circumstances and labour market |

External influences on employability |

USEM model of employability, Knight and Yorke (2002) updated in Yorke and Knight (2006)

|

U |

Understanding - Subject understanding |

|

S |

Skills - Including key skills and also known as skilful practice |

|

E |

Efficiency beliefs - Personal qualities and a belief that you can make a difference |

|

M |

Metacognition - To reflect upon learning and make/implement action plans as a result |

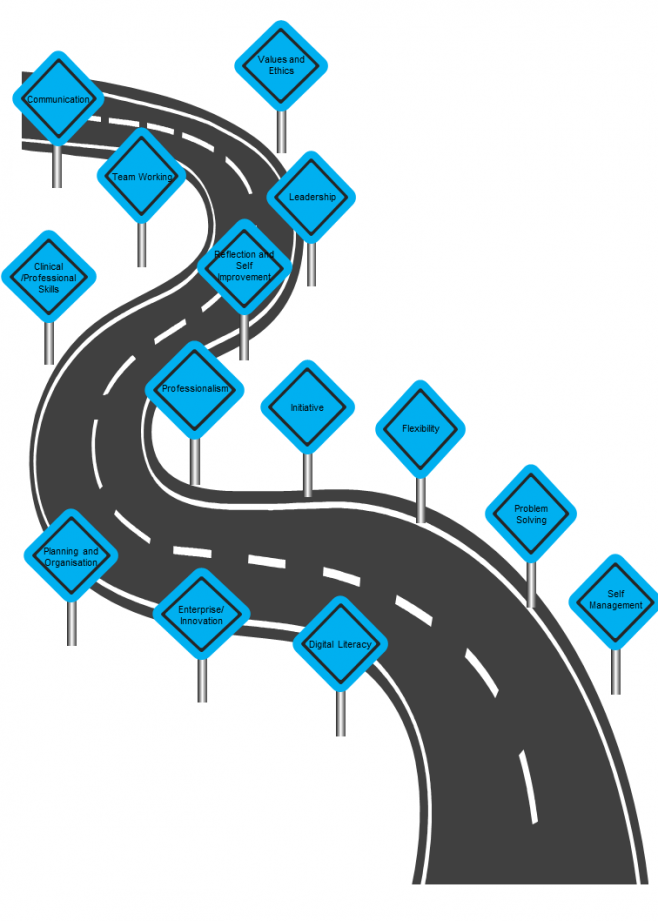

The employability roadmap for placements

Within practice placements – students are exposed to a wide range of employability opportunities that extend beyond the development of clinical/professional skills (CSP, 2020). The employability road map below represents a range of employability opportunities that students have within practice placements. It is evident that a variety of practice placement environments, from role emerging to digital placements can offer legitimate employability related learning that does not always have to be “face to face” (Taylor, 2020c). These signposts of opportunities for employability development within placements is not exhaustive, but the main areas identified in the literature, and captures the perspectives of all involved with employability.

The employability roadmap below (© Lisa Taylor 2020).

Communication – written, verbal and non verbal communication is vital for competence as a health profession, but also for employability (Trish and Fourie, 2016). Effective communication is essential as part of a team and for any form of leadership (Stanley, 2006), for example a student leading a service improvement task.

Values and ethics – the values and ethics of the profession, personal values and ethics and the organisation values and ethics are at the heart of being a health professional. An awareness and agency relating to values and ethics are fundamental to being a professional, and relate very closely to qualities relating to employability (Robinson, 2005). An individual awareness of the core values and beliefs that are important to them enables individuals to then explore employment opportunities with organisations with similar core values.

Team working – essential to develop as all health professions will be working within a team. Students need to be able to identify their own role within a team and their preferred team role. This awareness of team roles has been linked to job satisfaction (Ruch et al, 2018).

Leadership – there are a range of qualities that relate to leaders within health, including motivating, supportive, copes with change, flexibility, integrity, directing and helping as well as being clinically competent (Stanley, 2006). Leadership includes delegation and needs to be learnt as no one person can do it all themselves (Whitehead and Brown, 2017). Leadership is supported throughout an individual’s career (NHS, 2020a)

Clinical/Professional skills – placements offer students the opportunity to develop profession specific clinical and professional skills, but these do not always need to be face to face. Technology advances have enabled different models of placements to be delivered, facilitating clinical and professional skills, despite not being “face to face” or in a “clinical” setting. Click here to find out more about an example virtual practice placement. The diversity of roles available for students need to be represented within placement learning, and are not all “clinical skills”

Click here to find an innovative approach to placements blog and here for our placement expansion and innovation page

Reflection and Self Improvement – reflection was first reported in relation to professional activities (Schön, 1983) but is key for building employability and life long learning (Dacre-Pool, 2020; Parker and Badger, 2018). Reflection is a critical process to translate placement learning to the individual and their own learning, identity and futures (Rowley et al, 2015). Reflection aids individuals to gain a self identity and is key for integrating work with everything else that is in an individual’s life (Harrington and Hall, 2007), especially when work life balance is difficult (Parker and Badger, 2018).

Professionalism – although students are studying to become professionals, they need to be taught about professionalism (Mason, 2016). It is necessary to help students form pre professional identity helping to understand and connect between the reality and ideology of the student’s intended profession (Jackson, 2016), which is shaped by placement experiences (Wareing et al, 2017). Professional identity formation is a crucial part of employability and career development (Bennett, 2018)

Initiative – Initiative is important not only for performance within the placement environment and maximising their contribution to the workplace, but initiative has also been shown to result in higher employability and job satisfaction, and therefore should be supported and developed (Gamboa et al, 2009).

Flexibility – students need to be flexible within the workplace, to adapt to the changes that are constantly happening within health and social care, and is an essential part of employability soft skills (Succi and Canovi, 2019). Flexibility is consistently in the top attributes that employers are looking for in employees.

Problem solving – logic and judgement are key to help with problem solving, and are important within health professions, where individuals are having to constantly problem solve the patients/clients/services/research issues that they are presented with (Sisodia and Agarwal, 2017).

Planning and Organisation – planning and organisation is needed by every individual within the world of work – to maximise their efficiency and contribution to the team and is important employability characteristic (Sisodia and Agarwal, 2017).

Enterprise/Innovation – innovation is essential to help to facilitate change within service provision (NHS, 2020b), with transformation very much a part of day to day work within a constantly changing healthcare environment. There are opportunities for enterprise within the placement setting. Involvement in quality improvement is seen to help develop student’s careers (Jones and Olsson-Brown, 2019), with transferable skills for wider enterprise and innovation. The core skills that students learn from activities such as service improvement tasks are crucial building blocks for wider enterprise and innovation. Employability and enterprise and innovation are closely linked (Tibby and Norton, 2020).

Digital Literacy – technology enhanced learning is part of HEE’s strategy (HEE, 2020) and fast becoming an essential element of a health professional’s toolkit as telehealth takes off in light of Covid-19. Digital literacy more widely is emerging as a crucial employability focus (Bejacković and Mrnjavac, 2020)

Self Management – students need to be prepared for being able to manage themselves within the working environment, to aid their transition from being a student to an autonomous practitioner (Whitehead and Brown, 2017), managing themselves and their workload. The preceptor package also helps with this transition once qualified, but the principles can be applied to students on placement to support transition to autonomy (NHS Employers, 2020).

- Bejaković, P, Mrnjavac, Z (2020) The importance of digital literacy on the labour market. Employee Relations 42(4)

- Alt, D (2015) Assessing the contribution of a constructivist learning environment to academic self‐efficacy in higher education. Learning Environments Research, 18 (1), 47– 67

- Bennett, D (2017) Metacognition as a graduate attribute: Employability through the lens of self and career literacy. In Huda, N., Inglis, D., Tse, N., & Town, G. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Australasian Association for Engineering Education (214-221). Sydney, December 10-13

- Bennett, D (2018) Embedding employABILITY thinking across Australian higher education. Submitted July, 2018. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education and Dawn Bennett 54 Training. Retrieved from https://altf.org/wp‐content/uploads/2017/06/Developing‐EmployABILITY‐draft‐fellowship‐report‐1.pdf

- Bennett, D (2019) Graduate employability and higher education: Past, present and future. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 5, 31– 61. Retrieved from http://www.herdsa.org.au/herdsa‐review‐higher‐education‐vol‐5/31‐61

- Bridgstock http://www.graduateemployability2-0.com/

- Clouston, T, Westcott, L, Whitcombe, S (2018) Transitions to practice – essential concepts for health and social care practitioners M & K Publishing

- Cole, D, Tibby, M (2013) Defining and developing your approach to employability: A framework for higher education institutions Higher Education Academy York

- Crisp, G, Letts, W, Higgs, J (2019) Education for Employability (Volume 1) The Employability Agenda Brill Sense

- CSP (2020) https://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/thinking-differently

- Dacre Pool, L Sewell, P (2007), "The key to employability: developing a practical model of graduate employability", Education and Training 49(4) 277-289

- Dacre-Pool, L (2020) Revisiting the CareerEDGE model of graduate employability Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling 44 (1) 51-56 April 2020

- Elkington, S (2016) Teaching excellence, student success and the HEA framework series presented at Increasing Graduate Employability and Employment ICO Conference centre 19th May 2016

Fairley-Murdoch, M, Ingram, P (2017) Revalidation – A journey for nurses and midwives Open University Press McGraw Hill Education

- Gamboa, J, Gracia, F, Ripoll, P, Peiro, J (2009) Employability and Personal Initiative as antecedents of job satisfaction The Spanish Journal of Psychology 12(2) 632-640

- HEE (2020) https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/technology-enhanced-learning

- Harrington, B, Hall, D (2007) Career Management and Work-Life Integration – Using self-assessment to navigate contemporary careers Sage Publications Inc.

- Hillage, J, Pollard, E (1998) Employability: developing a framework for policy analysis Research Report RR85 Department of Education and Employment November 1998

- Hinchliffe, G and Jolly, A (2011) ‘Graduate identity and employability’, British Educational Research Journal 37(4): 563-584

- Hooley, T (2020) What to expect from graduate recruiters following Covid-19 – The employer’s perspective Panel discussion at The Graduate Employability Conference 24th June 2020

- Inkson, K, Dries, N, Arnold, J (2015) Understanding Careers Sage Publications Ltd

- Kay, A (2013) This is how to get your next job – an inside look at employers really want American Management Association

- Knight, P, Yorke, M (2002) Employability through the curriculum Tertiary Education and Management 8: 261–276

- Kubler, B, Forbes, P (2005a) Student employability profile: Health Sciences, Enhancing student Employability Co-ordination Team January 2005

- Kubler, B, Forbes, P (2005b) Employability guide Health Science and practice: allied health professions student employability profile, Enhancing student Employability Co-ordination Team April 2005

- Kubler, B, Forbes, P (2005c) Employability guide Health Science and practice: nursing student employability profile, Enhancing student Employability Co-ordination Team April 2005

- Jackson, D (2016) Re-conceptualising graduate employability: the importance of pre-professional identity, Higher Education Research and Development 35(5) 925-939

- Jones, B, Olsson-Brown, A (2019) How to get started in quality improvement British Medical Journal 364:k5408

- Mason, R (2016) in Taylor, L (2016) How to develop your healthcare career – a guide to employability and professional development Wiley Blackwell

- McQuaid, R, Lindsay, C (2005) The concept of employability Urban Studies 42(2):197-219

- NHS (2020a) https://www.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/

- NHS (2020b) https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/

- NHS Employers (2020) https://www.nhsemployers.org/your-workforce/plan/workforce-supply/education-and-training/preceptorships-for-newly-qualified-staff

- Parker, R, Badger, J (2018) The essential guide for newly qualified Occupational Therapists – transition into practice Jessica Kinsley Publishers

- Robinson, S (2005) Learning and Employability Series Two – Ethics and Employability The Higher Education Academy

- Rowley, J, Bennett, D, & Dunbar‐Hall, P (2015) Creative Teaching with Performing Arts Students: Developing Career Creativities through the Use of ePortfolios for Career Awareness and Resilience. In Pamela Burnard, & Elizabeth Haddon (Eds.), Activating Diverse Musical Creativities: Teaching and Learning in Higher Music Education (pp. 241– 259). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Ruch, W, Gander, F, Platt, T, Hofman, J (2018) Tem roles: their relationship to character strengths and job satisfaction The Journal of Positive Psychology 13(2) 190-199

- Savickas, M (1997) Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory The Career Development Quarterly 45(3): 247–259

- Savickas, M, Porfeli, E (2012) Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries Journal of Vocational Behavior 80:661–673

- Schön, D (1983) The Reflective Practitioner San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

- Sisodia, S, Agarwal, N (2017) Employability skills essential for healthcare industry Precedia Computer Science 122 (2017) 431-438

- Stanley, D (2006) In command of care: clinical nurse leadership explored. Journal of Research in Nursing 11 (1): 20-30

- Succi, C, Canovi, M (2019) Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers’ perceptions Studies in Higher Education https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420

- Super, D (1980) A Life-span, Life-space Approach to Career Development Journal of Vocational Behaviour 16:282-298

- Taylor, L (2016) How to develop your healthcare career – a guide to employability and professional development Wiley Blackwell

- Taylor, L (2020a) www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/employability-nature-and-nurture

- Taylor, L (2020b) https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/placements-post-covid-19-time-re-evaluation

- Taylor, L (2020c) https://blog.insidegovernment.co.uk/higher-education/peer-enhanced-e-placement

- Tibby and Norton (2020) https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/launch-embedding-employability-framework-guide

- Tomlinson,M (2017) Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability Education and Training 59 (4)

- Trish, L, Fouries, E (2016) Graduate Employability and Communication Competence: are undergraduates taught relevant skills? Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 79 (4) 442-463

- Wareing, M, Taylor, R, Wilson, A (2017) The influence of placements on adult nursing graduates’ choice of first post British Journal of Nursing 24 (4)

- Whitehead, B, Brown, M (2017) Transition to nursing – preparation for practice Open University Press McGraw Hill Education

- Yorke, M, Knight, P (2006) Learning and Employability - Embedding employability in the curriculum Higher Education Academy April 2006